33rd-annual potato workshop attracts region’s growers, industry leaders

Nearly 100 growers and industry leaders from across the region converged here February 27, 2015, for the 33rd-annual Western Washington Potato Workshop, sponsored by the Washington State Seed Potato Commission and Washington State University Skagit County Extension.

Speakers included several WSU- affiliated faculty and staff members, among whom was event organizer Don McMoran, WSU Skagit County Extension Director.

“Agriculture has changed a lot in Skagit County over the previous 33 years, but it is nice to know that the education WSU Skagit County Extension provides to growers has made an impact in the area of potato production,” McMoran said. “Processors have come and gone; but where those crops have fallen off, potatoes have filled a niche and allowed Skagit County to be a leader in food production for western Washington.”

The workshop featured presentations from WSU Mount Vernon agricultural science program leaders Debbie Inglis (vegetable pathology), who talked about recent developments in potato pathology research; and Tim Miller (weed science), who discussed prevailing weed issues.

The annual workshop is designed to help educate potato producers on the latest best-management practices of growing potatoes in western Washington.

“I have attended and presented at almost every workshop since 1990,” Inglis said. “It has been gratifying to see the continuity in attendance over the years. I also have enjoyed becoming better acquainted with other speakers from different parts of the United States and the world, and I always learn something new and relevant to my own potato disease research.”

This year, Inglis shared results from some of her program’s latest research projects, particularly on three diseases that can affect potato tubers: brown spot, silver scurf and Potato virus Y.

Miller’s presentation focused on herbicides used to control problem weeds.

“There are several different herbicides registered for use in potato, each with different abilities to kill various species of weeds known to be problems in area potato production,” Miller said. “I focused on the mechanism of action for these herbicides (how they kill the weeds) and which herbicides to use for which weed species.”

Follow-up information about the workshop is available from McMoran at dmcmoran@wsu.edu, 360-428-4270 x225.

Winter soil testing service helps spinach seed growers prep for spring planting season

During wintertime, it’s not the mice that may keep spinach seed farmers from settling into their long winter’s nap. It’s the microscopic creatures stirring underground that concern many growers as they plan for the spring planting season.

The culprit: Spinach Fusarium wilt, a crop disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. spinaciae, a fungus that can survive many years in soil even when spinach is not present, according to Washington State University Plant Pathologist Lindsey du Toit.

The winter of 2014-15 marked the sixth year du Toit’s WSU Mount Vernon vegetable seed pathology team helped growers learn about the risk of their fields fostering this potentially devastating disease, which research shows can cause severe economic losses in a spinach seed crop, with symptoms including leaf wilt, stunting, root necrosis and reduced seed yield. The timing of the bioassay gave growers a chance to identify their top choices for spinach seed crop locations before the next annual spring pinning meeting, when planting sites are designated by random drawing.

“During the winter, we offer a greenhouse soil bioassay to test fields for the risk of spinach Fusarium wilt,” du Toit said. “Our purpose is to help growers and seed company personnel identify fields that can be planted to a spinach seed crop in shorter rotations than the current recommended rotation of 10-15 years out of spinach. More importantly, the bioassay is intended to help identify fields that should not be planted to spinach seed crops because of a high risk of Fusarium wilt.”

Soil testing identifies risks

The three-month annual WSU Spinach Fusarium Wilt Soil Bioassay begins in early November and concludes with an open house for participants in mid-February. Spinach seed producers and growers bring in a 5-gallon soil sample from each field to be analyzed by du Toit’s research team, which this year included Vegetable Seed Pathology Program Leader du Toit, Scientific Assistant Mike Derie, Agriculture Research Technologist Barbara Holmes, and Service Worker Sarah Meagher.

The soil samples are partially dried, put through a soil shredder to break up clods and thoroughly mix the soil, and then mixed with limestone if requested by the grower. The prepared soil is then used to fill plots in which seed is planted of three parent spinach lines that range from highly susceptible to partially resistant to Fusarium wilt. Treatments are replicated four times for each soil sample.

“The relative susceptibility of spinach parent lines to Fusarium wilt is a major factor contributing to the risk of this disease, so the bioassay is based on the reaction of three ‘standard’ spinach parent lines (proprietary inbreds) that are highly susceptible (S), moderately susceptible (M), and moderately resistant (R) to the Fusarium wilt pathogen,” du Toit explained.

“We plant known spinach lines into the soil so we can help growers determine the risk of their crop in a particular field,” said Derie, who based on the most recent bioassay findings is responsible for assigning weekly disease ratings for each field from which a soil sample was provided. “Each 5-gallon sample brought in by growers and seed companies includes soil from different portions of the field from which the sample was taken. The idea is to set up an optimal environment for this soil-borne fungal disease.”

The planted seed germinates within a week; and within three weeks, symptoms of Fusarium wilt begin to show on the plants, he said. “If all the plants come out healthy, the field is considered low risk,” he said. “Nobody’s going to plant spinach in a high-risk field.”

Limestone yields temporary benefits

One way to help suppress the development of Fusarium wilt is to treat a susceptible field with limestone, a treatment studied by former WSU Mount Vernon graduate student Emily Gatch, who developed and validated the soil-based greenhouse bioassay as part of the Ph.D work she completed in plant pathology in July 2013 under du Toit’s leadership.

“The maritime Pacific Northwest is the only region of the United States suitable for production of spinach seed, a cool-season, day-length-sensitive crop,” du Toit said. “However, the acidic soils of this region are highly conducive to spinach Fusarium wilt. Rotations of 10 to 15 years between spinach seed crops are necessary to reduce the risk of losses to this disease. Raising soil pH with limestone partially suppresses spinach Fusarium wilt, but the suppressive effect is transitory, and the disease still limits seed crop acreage in the region.”

Gatch conducted experiments to assess the potential for annual applications of limestone for three years prior to a spinach seed crop to improve Fusarium wilt suppression compared to the level of suppression from a single limestone amendment, du Toit said. “She developed our soil-based greenhouse bioassay to characterize the spinach Fusarium wilt risk of soil samples submitted from stakeholders’ fields and explore the mechanism(s) of limestone-mediated Fusarium wilt suppression.”

What Gatch found was that annual applications of limestone for each of three years prior to a spinach seed crop were superior to a single limestone application for suppressing Fusarium wilt and increasing seed yield, du Toit said. “Through in vitroexperiments, she demonstrated that deficiencies of iron, manganese, and zinc, associated with an increase of soil pH following limestone addition to soil, can reduce growth and sporulation ofthe pathogen. Furthermore, greenhouse experiments in naturally-infested field soil indicated that reduction in availability of these micronutrients in limestone-amended soils reduced Fusarium wilt inoculum potential.”

One-of-a-kind service for growers

Gatch’s dissertation on Fusarium wilt was accepted for publication in the scientific journal “Plant Disease,” and her successors on the WSU Mount Vernon bioassay team have her to thank for their ongoing service to the spinach seed crop industry.

“Her research demonstrated relationships among soil properties and spinach Fusarium wilt development, increased the capacity for and profitability of USA spinach seed production, and will guide future research on soil-based management of this disease,” said du Toit.

The cost of this annual soil-testing service is $200 per field sampled by participating spinach seed growers and producers. According to Derie, that amount covers the cost of the labor and expenses involved in conducting the bioassay.

“No one else is doing this kind of service for growers,” Derie said. “It’s really a great deal for them, considering what it would cost to have invested in seed-bed preparation – ground work, herbicide treatment, fertilizer application, seed purchase and planting, and related labor and equipment – and then lose the whole crop to Fusarium wilt.

“The disease often won’t show up until the crop bolts (flowers),” he added. “And by then it’s too late and the growers and seed companies have lost their investment. What we’re doing through this soil testing service is giving them informed options for making decisions, like what seed lines to use and what fields to plant.”

WSU Mount Vernon blueberry workshop features pesticide alternatives

Two WSU Mount Vernon small fruit researchers spoke about alternatives to pesticide use at the Blueberry Workshop here February 11, 2015.

The all-day workshop was sponsored by the Northwest Center for Alternatives to Pesticides (NCAP). A $25 registration fee included lunch and seven presentations focused on organically managing blueberry crops.

WSU Mount Vernon Postdoctoral Research Associate Dalphy Harteveld, who specializes in berry pathology; and WSU Assistant Research Professor Bev Gerdeman, an entomologist, were among the workshop’s featured speakers who discussed organic ways to deal with small fruit diseases and pests that can be devastating to this region’s blueberry crops.

Harteveld spoke about environmental factors associated with the organic management of mummy berry and other blueberry diseases. Mummy berry disease is the result of an overwintering fungus (Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosum) which infects blueberry plants and transforms berries into shriveled-up “mummies” that fall to the ground and spread the fungus to developing buds in the spring.

“Mummy berry is a major disease of blueberries, with limited options for the organic grower,” Harteveld said. “This workshop presented detailed studies on factors involved in the disease cycle of mummy berry, cultural control methods and on the efficacy of current commercial products for the organic grower. Besides mummy berry, there was a session presenting other main and emerging blueberry diseases to watch out for this coming season and the options for organic control.”

Gerdeman discussed organic management of spotted wing drosophila in blueberry. Spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) is a soft fruit pest native to Asia which has become established in the Pacific Northwest. The female of this fruit fly species lays its eggs in the ripening berries, which hasten decay as the developing larva feed inside the fruit.

“Spotted wing drosophila continues to be a challenge for organic growers,” said Gerdeman. “We are currently working on ways to maximize efficacy of our organic tools, while blending novel cultural management techniques to create a reliable program for our organic growers.”

Other presenters included blueberry researchers from Oregon State University, a representative of Northwest Farm Credit Service, who discussed whole-farm revenue insurance; and an organic grower from Cascadian Farms, who shared his perspectives on sanitation, monitoring and managing. Weed management and mulching were also addressed at the workshop.

More information about future workshops is available at www.pesticide.org or by contacting NCAP Operations Manager Sarah Finney, 541-344-5044 ext. 19,agworkshops@pesticide.org.

Skagit Men’s Garden Club donates $5K to vegetable pathology research program

Professor Debbie Inglis got an early holiday gift December 4, 2014, when members of the Skagit Men’s Garden Club surprised her with a $5,000 donation to her WSU Mount Vernon Vegetable Pathology research program.

“I feel like the woman who won the Powerball Lottery,” said Inglis, who is the Vegetable Pathology program leader. “I know how hard the Club works to support agriculture research, and I will use the money very wisely.”

According to Club board member and past president Bob Case, such gifts are funded through the Club’s annual plant sales.

“Historically, proceeds from our plant sales were used to provide scholarships for horticulture students,” Case said. “A few years ago, when there were fewer applicants for the scholarships and our plant sales had increased, we decided to provide larger gifts to help support the research being conducted in this area.”

The Skagit Men’s Garden Club, which is open to both men and women, organized in 1972 and has been meeting monthly ever since, frequently at the Research Center. Some of the original members, now in their 90s, still regularly attend, Case said.

“We are honored to have such a dedicated group of individuals who have been volunteering their time throughout the decades to support agriculture-related education and research,” said WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director and plant breeder Stephen Jones. “This is a real demonstration of the Skagit Men’s Garden Club’s strong relationship over the years with the Research Center.”

More information about the Skagit Men’s Garden Club is available athttp://skagitmensgardenclub.wix.com/index#!

WSU Mount Vernon Extension specialist earns sustainable ag fellowship

WSU Mount Vernon Northwest Regional Livestock and Dairy Extension Specialist Susan Kerr is one of four national Extension educators selected as a 2015-2017 Sustainable Agriculture Fellow.

Kerr and the three other Fellows – from Missouri, Florida and Maine — were announced at this year’s National Association of County Agricultural Agents Conference in Mobile, Alabama. They were chosen from more than 40 applicants for the Fellowship, sponsored by Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education and NACAA.

The SARE/NACAA Fellows Program provides hands-on training to enhance understanding of sustainable agriculture and broad-based, national exposure to successful and unique programs in sustainable agriculture. Fellows participate in a series of seminars and visits to selected farms and ranches that expose them to sustainable farming and ranching systems, with a focus on basic sustainable agriculture strategies and how they work in the field.

“The SARE Fellows Program has a very good reputation for being a well-supported opportunity to investigate the nature of sustainable agriculture throughout the United States,” Kerr said. “Over the course of 2015 to 2017, we will tour farms in each of the four regions of the United States. I’m particularly interested in learning more about sustainable livestock production practices and thought this would be a good way to see what different people are doing in the South, Northeast, North Central and West parts of the country.”

According to Kerr, the Fellows Program provides extensive resource materials and learning opportunities, as well as experience educating others in sustainable agriculture practices.

“We’ll have reading and writing assignments, webinars, virtual discussions and other educational opportunities; and we’ll be expected to write publications and make presentations about what we learn,” she said. “In my application to the program, I mentioned the goal of developing a sustainable livestock curriculum; so I certainly hope to accomplish that – with the help of collaborators.”

“Dr. Kerr is the newest addition to our faculty here, and we are thrilled to have her learning more about and advancing sustainable agriculture practices in this region,” said WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director Steve Jones.

“Sustainability in agriculture involves environmental, societal and financial considerations,” said Kerr. “When we talk about livestock, we need to consider animal welfare factors as well. I hope to share what I learn and continue to learn from others through discussion sessions in which producers compare results of different management practices and share successes and challenges as they work toward sustainability, as they define it.”

More information about the SARE/NACAA Sustainable Agriculture Fellowship is available here.

Diggin’ the dirt

Third-grade students get a hands-on lesson in soil science

New berry pathology research team helps NW growers fight off fungal infections of small fruit crops

Northwest Washington’s small fruit growers may get some help warding off two growing threats to their high-value crops, as a result of the ongoing work of WSU Mount Vernon’s new berry pathology research team.

Associate Plant Pathology Professor Tobin Peever, Post-doctoral Research Associate Dalphy Harteveld, and Ph.D student Olga Kozhar are studying the biology, ecology and epidemiology ofBotrytis cinerea and Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi, fungi which respectively cause Botrytis gray mold and mummyberry of raspberry and blueberry. These two plant diseases are infecting and posing a significant risk of loss to the Pacific Northwest’s blueberry, raspberry and strawberry crops, valued at $136 million according to the most recent annual statistical information available from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“For both diseases, we are focused on similar questions,” said Peever, whose research is geared to identify how and when infection occurs, under what environmental conditions infection occurs, how disease cycles can be disrupted, and how disease spreads among different berry crops. “We are interested in providing growers with a better understanding of the disease cycles of these two important berry diseases, as well as other diseases, so that control methods can be employed more effectively and in a more cost-effective manner.”

Collaborative teamwork

The three researchers — part of a collaboration between WSU Mount Vernon and Washington State University’s Department of Plant Pathology in the College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences in Pullman — are working closely with local growers to determine how their research can address the needs of the community and the Washington state berry industry.

“Over the past eight months or so, we have met with several different grower groups and industry leaders to establish pathology research priorities,” Peever said. “These meetings will occur on a regular basis to continually update our priorities and obtain industry feedback as well as keep growers informed of our research progress.”

One of those priorities is to help small fruit growers more effectively deal with fungicide resistance.

“We are continuing a large survey of fungicide resistance to the major fungicides used to control Botrytis gray mold in blueberries, raspberries and strawberries, a project initiated by Alan Schreiber,” Peever said. “The objective is to provide growers with a much better idea of the status of resistance to the major fungicides used for disease control in these crops.”

According to Peever, it has been nearly 10 years since WSU has had a small fruit pathologist; and the need for berry pathology research is growing.

Reduced pesticide use

“Our main goal is to provide growers with increased knowledge of the disease cycles of these two diseases – Botrytis gray mold and mummyberry — and to ensure this knowledge will be directly applicable to improving disease control and allowing growers to move away from calendar-based application schedules,” Peever said. “We hope to be able to reduce fungicide use while maintaining a high level of disease control by using fungicides only when they are needed.

“Reducing the use of fungicides will have the added benefit of reducing pesticide inputs to the environment, lowering selection pressure for resistance to these fungicides and preserving their use for disease control in berries and other crops,” he said.

Peever and WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director Steve Jones anticipate this new berry pathology team will complement the work being conducted across the Pacific Northwest — within Lisa Wasko DeVetter’s WSU Mount Vernon small fruit horticulture program; at the WSU plant pathology labs in Pullman; in the fields of WSU’s cross-border agricultural research partner, Oregon State University, in the Willamette Valley; and in British Columbia.

Peever’s team is collaborating with OSU berry researchers Jay Pscheidt and Lisa Jones to address different components of the Botrytis gray mold disease cycle and with the British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture and food scientist Siva Sabaratnum on fungicide resistance in B. cinerea.

Holistic approach

“The region has been in desperate need of a berry pathology team, and we feel this is a great start to filling that need holistically,” said Steve Jones.

“Many berry pathology issues are only addressed by looking at the whole berry production system, which includes consideration of other pests and weeds as well as cultural aspects,” Peever explained. “Our pathology research intersects with many small fruit horticulture issues like plant phenology, nutrition, and irrigation; and we collaborate closely with Lisa DeVetter’s research program.”

“These are incredibly exciting times for berry research in the region, and we look forward to collaborations with researchers here as well as many others nationally and internationally during the next few years,” Peever added. “I think this influx of people researching berry problems in the Pacific Northwest bodes very well for the berry industry in Washington and the region.” Peever and his berry pathology team’s research are currently funded by the Washington Red Raspberry Commission, the Washington Blueberry Commission, the Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration, and the Northwest Center for Small Fruits Research.

Researchers, growers help rebuild soil to boost region’s table beet seed production

Western Washington seed producers, growers and researchers have found some common ground to help solve a long-term puzzle that has plagued their $2-million-per-year table beet seed industry: why the fields in this region are not as productive as they used to be. The key, according to WSU Vegetable Seed Pathologist Lindsey du Toit, is rebuilding the soil.

“Incrementally over time, most local beet seed growers have reported significant drops in their beet seed yields — some as much as 50 percent,” du Toit said. “With less seed available here, where 95 percent of the U.S. beet seed crop is produced, some seed companies started taking beet seed production contracts overseas to obtain enough seed to meet the growing worldwide demand for beets.

“That has had an adverse economic impact on Skagit Valley farmers, who are paid based on the quality and quantity of seeds they produce,” she added. “But you can’t blame the seed companies, because seed is their bread and butter.”

The drop in beet seed production, du Toit said, is the result of a combination of factors that came to light last winter, when growers, seed company representatives and researchers met at the WSU Mount Vernon Research Center to share their observations – and a few frustrations.

Collaborative effort

“Initially, there was a lot of finger pointing going on,” she said. “Some people suspected diseases, such as Verticillium wilt, which is not uncommon in this region. Others were looking at weeds and possible injury from using herbicides that have recently been approved to control them.”

It wasn’t until she started meeting with local growers and seed producers, who inspired her to think beyond her specialized role as a plant pathologist, that du Toit began to fit together the pieces of the decreased beet seed yield puzzle.

“It helped that I was hearing such a diversity of stories and gaining empirical evidence about what was happening in the companies’ seed beds on Whidbey Island and in the farmers’ beet seed fields across the valley,” said du Toit.

“Yes, there was some Verticillium wilt and other diseases and pests present in some areas, and some herbicides were impacting certain parent lines of beets;” she said, “but the much bigger issue I observed across the board was that by mid- to late-summer, these fields all had very severe moisture stress and nutrient stress.”

Those stresses are a result of the breakdown of soils, which need adequate structure to retain moisture during dry periods and allow plants to obtain the water, nutrients and root development required for vigorous crop production, du Toit explained.

Paradigm shift

“Our soils here have a history of being very productive and rich in nutrients, but they are not as rich or forgiving to the extent that they were in the past,” she said. “The longer and more you work the fields, the more the soils break down; so now they cannot hold moisture and nutrients as well as they did to produce high-yielding crops.

“For example, rototilling destroys soil structure over time, but this practice has become integral to the annual production of high-value crops like fresh-market potatoes, which have become a major crop in this region,” she said. “At the same time, we have lost the benefits of cover crops and other crops, such as pea and pasture grass, which used to be grown widely but have declined severely in acreage as a result of the loss of local vegetable processing plants and a reduction in the number of dairy farms.

“Farming in the (Skagit) Valley is going through a paradigm shift,” said du Toit. “Now we need to look at ways to rebuild the soils which we have depleted over time.”

To help begin that soil replenishment process, du Toit, WSU Skagit County Extension Director Don McMoran, WSU Whatcom County Regional Extension Specialist Chris Benedict, and WSU weed scientists and entomologists have been working with beet seed farmers across the region.

Understanding stress

During each month of the growing season, farmers brought in beet leaf samples for du Toit to send to a soil and plant testing lab, so any nutrient deficiencies could be detected and treated using foliar feeds.

WSU Mount Vernon Weed Scientist Tim Miller conducted on-farm trials with herbicides to identify which might be damaging parent lines and which are most effective for weed control, while Entomologists Lynell Tanigoshi and Bev Gerdemanexamined beet seed crops for insect and mite pests impacting seed production.

To better understand the soil moisture stress throughout the beet-seed crop’s biennial growing cycle, in spring 2014 McMoran set up a monitoring process through which twice-monthly soil moisture status data were collected from a local field, allowing growers to see when fields were going into periods of moisture stress before the crops might show stress-related symptoms, such as wilting.

“This gives farmers the information they need to time irrigations to provide relief during the drier mid-June to September period, when crops are being pollinated and need energy for flowering and seed set,” du Toit said.

Encouraging results

Benedict recently began meeting with beet seed growers to assess cover crops and other soil amendments, such as composts, as economical means to supply carbon and other minerals needed in soils for adequate nutrition and greater soil tilth necessary for their crops to withstand drier periods during the growing season.

“There was empirical evidence that soil amendments dramatically increase the quantity and quality of beet seed crops,” du Toit said. “As a result of collaborative trials with growers to research this in local farmers’ beet seed crops over the past few years, growers are now considering long-term investment in composts and cover crops such as mixes of cereals — rye, barley, oats – with nitrogen-fixing crops, like clovers and vetches, that are cold-tolerant and can provide sufficient biomass as winter cover crops.”

Early reports from the field indicate these collaborative trials have been productive, according to du Toit.

“I just heard from one grower who said the seed germination increased from 4% in last year’s crop to 95% for this year’s crop of the same variety of beet,” she said. “The main things he is doing differently include irrigating and foliar feeding based on the moisture stress and monthly foliar analysis data we provided.”

Long-term investment

Another grower reported an increase in seed yield of 500 pounds per acre for a crop which was irrigated, foliar fed, and grown in soil that had a rye cover crop for two years to help improve soil health, compared to the same variety grown in an adjacent field that had no preceding cover crop.

“That’s huge,” said du Toit. “Such extreme results may not turn out to be indicative of the norm, but they are really encouraging.”

Looking ahead, du Toit and her colleagues are optimistic about the potential for reduced moisture and nutrient stress and increased crop production as a result of soil-building efforts throughout Skagit, Whatcom, Island and Snohomish counties.“It’s exciting to see growers looking at irrigating, foliar feeding, adding compost, and using cover crops,” she added. “The challenge for us all moving forward is how to help work out agricultural systems that farmers can use to rebuild soils and still make a profit. It’s not going to happen overnight. It will entail long-term investment in our soils.”

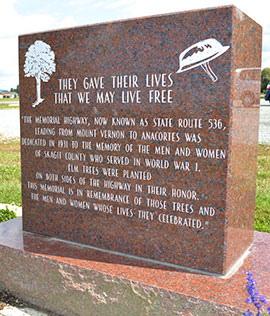

9/11 Ceremony at WSU Mount Vernon rose garden to honor WWI veterans

Mount Vernon Mayor Jill Boudreau led a ceremony to honor WWI veterans here September 11, 2014, at the Discovery Garden adjacent to Memorial Highway.

The event, which was open to the public, was sponsored by the Veteran Monument Project, according to event organizer/moderator Rich Sundance, a retired U.S. Navy Chief who now serves as commander of the local Disabled American Veterans’ community based outpatient clinic in Mount Vernon.

“This was a commemoration of the 100-year anniversary of the start of World War I (which broke out July 28, 1914),” Sundance said. “It was planned in conjunction with other 9/11 events to celebrate the lives of veterans who sacrificed it all for freedom.”

The ceremony was held at the site of the World War I Veterans Memorial, just west of the WSU Research Center, in the circular arbor in the rose garden, a public display garden maintained by the volunteer Master Gardeners with Washington State University’s Skagit County Extension program. The memorial was placed here in 2008 to restore the significance of Memorial Highway, which was dedicated in 1931 to honor Skagit County citizens who gave their lives in World War I.

Included in the remembrance ceremony were the Whidbey Island Naval Station Honor Guard, which provided the presentation of the Colors; Pastor Ron Deegan, of Mount Vernon’s First Baptist Church, who performed the invocation and benediction; local realtor Duane Gish, who recounted the history and significance of the WWI monument; residents Eric Stendahl, Scott Heiner and Dawn Hardman, who read the veterans’ names; drummer Emma Sundance; and Stan Relyea, who performed Taps.

“We are honored to have the memorial housed here at the Center,” said WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director Steve Jones. “It is our responsibility to not let these brave souls be forgotten.”

The WWI memorial at WSU Mount Vernon is one of six monuments in the Skagit Valley which have been or will be restored through the Veteran Monument Project, according to Sundance, who also spearheads that non-profit project.

Sundance said the other five memorial sites dedicated to veterans he has identified in Skagit Valley are Causland Memorial Park (World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War), 710 N Avenue, Anacortes; Monument to Joseph Berg (World War I), in Pine Square, downtown Mount Vernon; Statue of Chief Warrant Officer 2, Douglas Vose III (Operation Enduring Freedom, International Security Assistance Forces, Afghanistan), at Concrete High School, 7830 S. Superior Ave., Concrete; Bayview Cemetery, off Bayview Edison Road in Mount Vernon; and the historic Cannon (Civil War or Spanish-American War) in front of the steps of the Skagit County Courthouse, 700 S. 2nd Street, Mount Vernon.

“This whole monument restoration process has instilled new life in many of the old-timer veterans who have joined in the effort to help clean up our local gravestones, markers and monuments,” Sundance said. “It’s a real heart-felt thing to do.”

More information about the Veteran Monument Project is available athttp://mawords.com/veteranmonumentproject.org.

WSU Mount Vernon plant pathologist elected to national council

WSU Mount Vernon Vegetable Seed Pathology Program Leader Lindsey du Toit has been elected as 2014-2017 councilor-at-large of the American Phytopathological Society.

The national council serves as the governing body of APS, which is comprised of plant pathologists representing a broad range of specialties in higher education, government, industry and private practice. The society advances high-quality, innovative plant pathology research and the sharing of scientific innovations worldwide.

As councilor-at-large, du Toit will help the council provide oversight to the APS membership. Her role includes working with the various regional divisions and international members and assisting with planning and organizing the annual national meeting, which will be held in August in Minneapolis.

“I was pleasantly surprised by this vote and the recognition from my peers,” said du Toit, who is one of approximately 5,000 members of the professional society and has served in committee leadership positions.

“Looking at the bigger picture will be new to me,” she said. “My goal is to learn as much as I can from the people who are experienced in this position and evolve into the role so I can provide perspective into the vision and decision-making.”

Mentoring will be a focus throughout her three-year term.

“I have a lot to learn from my mentors, and I hope to establish a more diverse, extensive network and engage more of the membership as I evolve into this role and begin to mentor others,” she said.

According to du Toit, her experiences as a WSU plant pathology professor and APS leader are mutually beneficial in her new role within the society.

“Being elected as councilor-at-large brings very good visibility to WSU, and the perspective I bring to the APS council from an applied program in research and extension brings benefits to the society as a whole,” said du Toit.

Her election was not such a surprise to her fellow researchers and colleagues.

“Lindsey is one of the most highly respected scientists that I know,” said WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director Stephen Jones. “That is true with growers, industry, students, staff and faculty. She also has a very strong reputation, nationally and internationally, as her election to the APS Council acknowledges. We here at the research center and WSU as a whole are very lucky to have her as a member of the team.”

More information about the American Phytopathological Society is available athttps://www.apsnet.org/Pages/default.aspx

Federal excess property association honors Administrative Manager Jeanne Burritt

WSU Mount Vernon Administrative Manager Jeanne Burritt had no idea she was the honoree when she stepped forward to photograph an award winner at a professional conference June 17 at the University of Missouri in St. Louis.

Jesse Smith, President of the Users and Screeners Association — Federal Excess Personal Property, Inc., asked her to get a snapshot and then handed her a plaque recognizing her 20 years of service to the association, which loans U.S. government-owned equipment for research purposes to land-grant universities such as Washington State University.

“It totally caught me off guard,” said Burritt, who is a past secretary and for the last six years has served as Association treasurer. “I thought I was just there to take a picture, and then they called my name.”

The award acknowledges Burritt’s “outstanding recognition and thanks” for her “support in orchestrating the needs” of the Association, which she joined in the early 1990s when assisting with paperwork for acquiring excess property for the WSU College of Veterinary Medicine and the WSU Business Office in Pullman.

After five years, she became secretary of the Association and has since served on the board, planning workshops and overseeing correspondence between the 50 members from across the United States and Guam. When Burritt moved to the WSU Mount Vernon Research Center in 2007, as the Accountable Property Officer she started the Federal Excess Personal Property Program and that year was elected as the Association’s treasurer.

She organized the annual conference last summer at WSU Mount Vernon and has already begun planning for next year’s conference, which will be held in April at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

“Because we are focused on agriculture research, we try to schedule our annual conferences so they don’t occur at the busiest times of the growing season,” said Burritt. “That way, more of our members are able to attend.”

Meeting and exchanging expertise with other members is a real perk of the job, she said.

“It’s really a great opportunity to interact with other people who deal with excess property in their organizations,” Burritt said of her volunteer work on behalf of the Association. It broadens my knowledge and helps me find better ways for dealing with federal excess personal property here at WSU Mount Vernon.”

Acquiring federal excess personal property on loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Federal Excess Personal Property Program benefits WSU and its Mount Vernon research programs, according to Burritt.

“Our researchers can acquire farm machinery, microscopes and other research-related equipment this way rather than purchasing those items outright, so they save money for their research programs,” she said.

“WSU benefits greatly from this program, and a big part of the reason for that is the work that Jeanne does,” said WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director Steve Jones. “We are fortunate to have her here and involved in procuring excess property for our research.”

More information about the Users and Screeners Association — Federal Excess Personal Property, Inc. is available at http://www.usa-fepp.org/Home_Page.html

WSU Mount Vernon Field Day features tour, talks, research updates and BBQ

More than 100 people turned out July 10, 2014, for WSU Mount Vernon’s annual Field Day, which featured a tour, research project updates, and an agricultural community barbecue.

The event, which was free and open to the public, kicked off with a walking field tour of nearly 100 acres of the Center’s active research plots. A tractor-driven wagon provided respite for those who opted to catch a ride for the 2 ½-hour tour.

Faculty members and graduate students representing the Center’s current research and Extension programs were hand to talk about their current projects and how their work impacts the region’s growers, consumers, agricultural businesses, and local economies.

“We have had these field days here since the 1940s, and it is a great opportunity for us to show what we do to help the region,” said Steve Jones, WSU Mount Vernon Research Center Director. “It also allows us to thank the many people and groups such as the Port of Skagit County, the Northwest Agricultural Research Foundation, and the many growers and industry representatives that fuel our research and contribute to our mission.”

WSU Mount Vernon’s mission is to serve the agricultural, horticultural, and natural resource science interests of the state through research and extension activities that are enhanced by the unique conditions of northwestern Washington: its mild, marine climate, rich alluvial soils, diverse small and mid-sized farming enterprises, and unique rural-urban interface.

Brief Field Day presentations highlighted the Center’s eight research programs: plant breeding, small fruit horticulture, entomology, vegetable seed pathology, vegetable horticulture, vegetable pathology, weed science, and dairy and livestock.

Field Day concluded with a chicken barbecue dinner, during which attendees visited with others in the agricultural community. Those working toward pesticide recertification received two credits through the Washington State Department of Agriculture.

Jones said he was pleased with the crowd of agriculture supporters – as well as the warm weather and sunshine – which emerged for this year’s Field Day.

“Every year, more people from across the region seem to turn out to catch up on what’s happening in the agricultural community and learn more about how our research impacts them and the local economy,” he said.

Monorail Bunny springs into WSU Mount Vernon

The Seattle Center Monorail Bunny made a spring-time 2014 stop at WSU Mount Vernon, where it learned about agriculture, horticulture and science. First stop was the greenhouse, where Vegetable Horticulture Program Leader Carol Miles and her grafting team demonstrated how they produce more vigorous, healthy and disease-resistant plants. It also spent some time studying heirloom dry beans with graduate student Kelly Ann Atterberry, whose master’s project focuses on pulse crop nutrition education for K-12 students. Last stop on the Bunny’s agriculture adventure was The Bread Lab, where it got a taste of local whole-wheat baking from Research Center Director Steve Jones and resident baker Jonathan Bethony.

See more photos from the Bunny’s Mount Vernon visit here.

The Monorail Bunny was left behind on a Seattle Monorail train in 2013 but has been on a lot of adventures — including visits to the Pacific Science Center and Pike Place Market — while awaiting reunion with its owner. Read more about the Monorail Bunny’s adventures at http://www.seattlemonorail.com/events-and-news/monorail-bunny/

Local wheat breeder, new regional varieties focus of 2014 Small Grains Field Day

New varieties of wheat adapted for the mild marine climate of the Pacific Northwest were the focus of this year’s WSU Mount Vernon Small Grains Field Day. And there were plenty of samples on hand to highlight the range of color, flavor and aroma these regional wheats bring to the table.

At the top of the list was the Edison wheat, a hard white spring wheat selected from long-time Bellingham plant breeder Merrill Lewis’ Fossum Remnants 2012 seed plantings.

The Fossum Cereals wheat lines, and the Edison variety selected from them, are a testament to Lewis’ perseverance far afield from the lecture halls of Western Washington University, where he worked full time as an English professor from 1962 until his retirement in 1994. His education includes a bachelor’s degree in English, a master’s degree in history, and a Ph.D. in English/American Studies; yet he has no formal training in the plant-breeding sciences.

“Over the years, my ‘hobby’ has turned into a full-time job in itself,” Lewis said of his wheat breeding experience. “Maybe it’s the history buff in me, but I am fascinated by what I have learned from the work and writings of other breeders, farmers and researchers.”

That feeling appears to be mutual.

“This year we want to showcase Edison wheat, in honor of Dr. Lewis’ amazing contributions over the years to plant breeding research throughout this entire region,” said Steve Lyon, senior scientific assistant in the WSU Mount Vernon plant breeding program.

The name Edison in turn honors the Skagit County town at the end of Farm To Market Road and its local food lore, according to Lewis.

“The story given to me was that Edison had once been a shipping port for the Puget Sound,” Lewis said. “The problem was (through diking and draining to improve farmland), they changed where the Samish River went. Taking the river away from Edison cut off the boats that used to ply the Puget Sound and pick up foodstuffs from the Skagit Valley.

“I realized the name deserves some posterity,” he said. “Of course there’s another Edison who’s also known historically, and I thought we’ll just ignore him.”

This history of Edison – the town and the wheat – symbolizes its durability, the researchers agree.

“It takes 10-12 years to develop a wheat, and the wheat lines Dr. Lewis has developed and shared with us has saved us a lot of time and given us more to select on here,” said Lyon, who was surprised with an award acknowledging his decades of service to WSU plant breeding. The WSU Barley and Alternative Crops Breeding Program presented him with a certificate noting the latest feed barley, ‘Lyon,’ named in his honor.

Sharing commendations as well as research is an integral part of the breeding culture espoused by Lewis and WSU Mount Vernon Small Grains Field Day organizers. Whether it’s providing seed to farmers, amassing knowledge among researchers, or opening new niche markets for millers, bakers and maltsters, it’s all about the collaboration that helps promote sustainable, high-quality, high-yield, disease-resistant small grains production in the Northwest.

“Share and share alike — that’s the principle at the level of breeders,” Lewis said. “Some of this has changed over the years, as private companies and universities become more proprietary in their acquisition of seed lines, but the idea here is to keep the germplasm alive and make it available.”

According to Lyon, there are several promising wheat varieties with the potential to grow well and be successfully utilized here on the west side of the Cascade Mountains.

“The focus with small grains has been to bring in new established varieties to this area,” Lyon said. “Right now we’re looking at some really nice lines – the ones like Edison from Dr. Lewis, as well as some hard red and soft white winter wheats from private European companies, and some spring varieties through CIMMYT which do well in high rainfall areas and are especially good for bread wheat.”

CIMMYT is the Spanish acronym for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, a non-profit organization based in Mexico that researches sustainable development of wheat and maize farming worldwide. It provides seed, agronomy and agriculture research products, services and related tools to farmers in developing countries and maintains a seed bank which makes seed freely available to researchers.

At WSU Mount Vernon, plant breeding researchers grow and test the seed to determine suitable grains for this climate. In The Bread Lab, they take testing to the next level to determine the qualities of local small grains that make them desirable for milling, baking and malting purposes.

Bakers are attracted to Edison wheat because of its rich flavor and baking properties, Lyon said.

“There is a lot of research going on right now, including breeding barley, oats, buckwheat and dry beans,” he said. “And it all ends up in The Bread Lab. It can work in the field, but someone has to eat it.

“We try to test for both successes and failures, so you can get rid of a variety before it fails on the farmer,” said Lyon. “From large-scale farmers to those who just want to grow enough grain in their back yard to bake a loaf of bread, there is something for everybody here.”

WSU Mount Vernon graduate student brings taste of dry bean education to local fourth-graders

May 2014 was Dry Bean Month in the Whatcom Farm-to-School program and, as part of the focus on nutrition, a WSU Mount Vernon graduate student gave several fourth-grade classes a taste of what that colorful pulse crop is all about.

“We offered our lessons as part of the enhanced curriculum the Farm-to-School program provides to teachers with regard to the crop of the month,” said Kelly Ann Atterberry, a second year master’s student at WSU Mount Vernon. In her first year, she worked with students in Ferndale and Bellingham. This year, she is working with Kendall and Anacortes students.

“This is all about bringing awareness to the schools, where through the National School Lunch Program many children are served meals that must comply with U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Nutrition Standards for School Meals,” Atterberry said.

The U.S.D.A. healthy food standards include serving one-half cup of pulses per student each week. Pulses are part of the legume family – plants which have seeds enclosed in a pod — and include dried peas, edible beans, lentils and chickpeas. Pulses are high in protein and fiber (approximately six times that of brown rice) and low in fat content, according to Atterberry.

“Dry beans are wonderful because they are a vegetable and a source of protein, and the bean seeds come in a rainbow of colors, which are not only beautiful to look at but provide various phytonutrients,” said Atterberry. “But not many children are familiar with them as a food choice.

“Through our STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) based curriculum for fourth graders, we are demonstrating to students, teachers and parents that dried beans are inexpensive, taste very good, and are easy to grow,” she said.

Under the tutelage of her WSU Mount Vernon faculty advisor, Vegetable Horticulture Program Leader Carol Miles, Atterberry developed the School Garden-Based Education Program as part of her M.S. thesis, titled “Nutrition Education and School Garden Projects with K-12 Students to Promote Consumption of Pulses.”

According to Miles, the WSU Mount Vernon school garden curriculum is the only one in the United States that focuses on pulses.

“Utilizing dry beans in a school garden-based education program provides a unique opportunity to focus on improving the health of our school children, many of whom are suffering from diet-related conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease,” Miles said. “The challenge is, how do you get kids to eat what’s good for them?”

The school garden-based education program takes on that challenge, starting with three lessons geared to the summer dry bean planting season, May 15 through June 1. In Lesson 1, Predicting Germination, the students plant and observe the bean seeds. In Lesson 2, The Bean Life Cycle in the School Garden, students calculate the percentage of germinated seeds. Lesson 3, Classroom Activity on Dietary Fiber, includes nutrition education in the classroom and focuses on measuring and graphing plant height in the school garden.

The curriculum is comprised of those hands-on lessons as well as a cooking video; recipes including a Midnight Black Bean Cake that got an A-plus grade from faculty, staff, and student taste testers; and a WSU Extension fact sheet geared to parents and teachers on “Growing Dry Beans in Home Gardens.”

“Our curriculum combines nutrition education with math and biology activities that get the students excited about trying something new outside the traditional classroom setting,” Atterberry said. “What’s great about the pulse cooking demonstration video (available on YouTube) is that the kids can use it at home and get their parents involved.

“The more times the students are introduced to a new food, and the more familiar they become with it, the more likely they are to try it when it’s offered to them through the school lunch program,” she said.

During May 2014, Atterberry presented the curriculum materials to a total of five fourth-grade classrooms — two classes in the Mount Baker School District at Kendall Elementary School, where according to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Washington State Report Card 98.9% of the students receive free or reduced-price meals; and three classes in the Anacortes School District at Mount Erie Elementary School, where 30.4% of the students receive free or reduced-price meals.

Although Mount Erie Elementary is not part of the Whatcom Farm-to-School program, Atterberry said, she was invited to share her curriculum there after a master gardener with the Anacortes Community Gardens recommended it to one of the fourth-grade teachers. A graduate from the Anacortes School District, Atterberry especially enjoyed working with students in her old stomping grounds, she said.

“Our goal by fall is to have 10 classrooms working on the next phase: harvesting and threshing,” Atterberry said. “What’s really important is that we’re getting the word out that beans are really nutritious, and they taste good.”

They are also quite versatile, as Atterberry and artist Chris Nickerson of Anacortes have fashioned a jewelry business, Whole Fashion Farms, through which they have created a line of earrings, necklaces and rings featuring several varieties of dry beans.

More information about the WSU Mount Vernon School Garden-Based Education Program and links to the pulse recipes, cooking demo, and WSU Extension fact sheet are available at http://vegetables.wsu.edu/schoolgarden/

Whatcom Farm-to-School information is available athttp://www.whatcomfarmtoschool.org/

Meet WSU Mount Vernon’s new Small Fruit Horticulture Program Leader, Lisa Wasko DeVetter

Spring marks a fresh start for the Small Fruit Horticulture Program at WSU Mount Vernon NWREC, as native Iowan Lisa Wasko DeVetter joins the faculty as an Assistant Professor of Research and Extension here, after completing her Ph.D project in cranberry yield at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

With a B.S. in biology and horticulture and M.S. work focused on evaluating alternative weed management practices in vineyard production systems and their effects on weed control, grapevine production and soil quality at Iowa State University, Lisa brings a new depth to small fruit horticulture research and extension in the Skagit Valley and surrounding region. She looks forward to engaging the community and learning more about Pacific Northwest fruit production, with the overall goal of promoting sustainability within fruit production systems.

Here are a few of her thoughts on her new job here as Small Fruit Horticulture Program Leader.

- What is your official start date?

Officially, I start March 1, 2014. In my excitement, however, I have already begun discussing ideas for projects and laying the foundations for my future research and extension program.

2.What most attracted you to this position?

Many aspects of the position are both professionally and personally appealing. To name a few, the specific crops, people, and associated industries are of great interest. Visiting Washington and meeting future colleagues has only fueled this interest. The position is also perfectly aligned with my professional vision of building a high-impact research and extension program in small fruit production and physiology. Aligned with this vision is having a program that helps meet the needs of its stakeholders through a programmatic approach that closely partners research with extension activities. The research opportunities are also attractive given my interests in investigating sustainable production practices through an approach that takes account of the integrated nature of biological, environmental, economic, and social systems that affect fruit production. Furthermore, this position is well-poised for success given the support of the industries, university system, and other potential collaborative bodies. At the personal level, I am very excited to live in the Pacific Northwest. As a native Iowan, the opportunity to live, work, and raise my family in such a scenic community is a dream come true!

3. Describe the key components of the job, as you see it.

One critical component will be the establishment of a research and Extension program that is high-impact, complementary to other existing programs, and meets the needs of stakeholders. Accomplishing this will require building relationships and bringing together relevant groups that are representative of the small fruit industry.

4. What are some of your plans for moving forward with the Small Fruit Horticulture Program here?

One of my first tasks will be to collect input from associated industries, colleagues, and other peers as to what are the primary areas in need of research. With this information, I will move forward on building a program that addresses those needs. A few good candidates for research activities include (but are not limited to): investigating alternative practices to fumigation, evaluating the impacts of production practices on plant productivity, fruit quality, and soils, assessing the economic viability of production practices, investigating methods to enhance pollination and fruit set, and developing approaches for effective cane management in raspberry production. Additionally, I want to contribute to enhancing the pathology component of the program through strategic collaborations. I also want to develop informative resources for growers, which includes a small fruits website, workshops, field days, conferences, and other opportunities for professional development.

5. Tell us a little bit about your background and experience and how it all relates to the work you will be doing.

My first experience with horticulture was at my grandmother’s farm, located in northwestern Iowa. I never considered a career in horticulture until I went to college and got my BS at Iowa State University (ISU) in biology and horticulture. By that time, I came to the realization that I could actually study what I had a passion for – fruit crops. Moreover, I could contribute to promoting sustainability within small fruit horticulture through a career in research and extension. This led me to get a MS at ISU in horticulture and soil science, whereby I studied the effects of alternative weed management practices in Midwestern vineyards. This project exposed me to a systems-based approach to research in which I measured multiple variables in order to discern treatment effects on weed management, plant productivity, fruit quality, and soil quality. My PhD research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was also holistic. The main project of my program was a synthesis of how genetic, physiological, and environmental factors influence yield components of cranberry. This project was extension-based and occurred entirely on commercial cranberry farms. I also completed several physiological studies on cranberry, which contributed to my breadth in knowledge of plant systems. These experiences have left me with a broad understanding and appreciation for the many scales and nuances influencing fruit production. Having these diverse experiences will help me better serve the industry through a diverse and systems-based approach to research.

6. What would you like readers to know about you personally and about your management style professionally?

Most people would define me as ambitious and hard-working. I am also very open, easy-going, and have a strong passion for fruit science and promoting sustainability within our food systems. Furthermore, I really value the relationships I form with people. My management style is to be transparent and have those around know that they are valued as both an employee and individual.

7. What do you see are the major benefits of the WSU Mount Vernon Small Fruit Horticulture Program to farmers, growers, educators and the community in general; and how will you reach out to and interact with them in the course of your work here?

One of the major benefits is that this program will be driven by the ultimate goal of promoting sustainability in small fruit production within the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Thus, expect to see a very active program with a diversity of research projects that seek to address this goal. Also, I favor a transparent, collaborative, and participatory approach to research that includes the involvement of stakeholders and other peers. There are virtually no limits as to how people can contact me, whether it be through a stop by the (WSU Mount Vernon Northwestern Washington Research and Extension) Center, an email, phone call, and so on. I will also personally reach out at conferences, field days, and any other venue that permits me to interact with stakeholders.

Dr. Lindsey du Toit has been promoted to Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist. Dr. du Toit was hired by WSU as assistant professor and vegetable seed pathologist in August 2000, and has been based at the Mount Vernon NWREC since that time. In 2006, Dr. du Toit was promoted to Associate Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist. The focus of her internationally-recognized program is the etiology, biology and management of diseases that affect vegetable seed crops grown in the Pacific Northwest.

Dr. Lindsey du Toit received the Syngenta Award from the American Phytopathological Society. This award is given by Syngenta Crop Protection to an APS member for an outstanding recent contribution to teaching, research, or extension in plant pathology.

Dr. Tim Miller received the Presidential Award of Merit from the Western Society of Weed Science for his demonstrated and continued distinguished service to the society.

Amy Salamone (PhD student with Dr. Debbie Inglis) has been selected to receive the prestigious Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS) Scholarship from the ARCS-Seattle Chapter. ARCS Foundation is an organization of 17 Chapters serving 53 of the nation’s premier research universities. Nationally, over $82 million in financial support to more than 14,000 students has been awarded. The Seattle Chapter, founded in 1978, currently supports 121 PhD candidates at the University of Washington and Washington State University, and has contributed $13 million to 1000 talented scholars at these two research universities.

Charles Coslor, MSc student in the Entomology program, was selected to receive this year’s Louis W. Getzin Memorial Scholarship. Competition was fierce this semester for these endowment funds, which will support travel to the National Entomological Society of America meeting in Knoxville, TN, November 11–14, 2012. Charlie will present his research paper entitled Management of Drosophila suzukii through systemic activity of neonicotinoids on highbush blueberry. He will also present a poster entitled Systemic activity of neonicotinoids on Drosphila suzukii in blueberry for general submission at the national meeting.

Jeanne Burritt, Administrative Manager, received the 2012 Administrative Professional Contribution Award in recognition of exceptional contributions and service to WSU. Jeanne has worked for WSU for 31 years, 5 of those with WSU Mount Vernon NWREC. She was nominated by 5 different faculty and staff members.

Dr. Thomas Walters, Assistant Professor, was interviewed on the AgInfo.net radio program “Fruit Grower Report” to discuss his work on raspberry fumigation trials.Listen to the interview.

WSU Mount Vernon Research Center is proud to announce that this spring four of our graduate students have been awarded scholarships and or Fellowships:

Karen Hills, PhD student in the wheat program was awarded a $1000 scholarship from the Roscoe and Frances Cox Scholarship Fund. Her research involves soil fertility issues affecting the quality of organic bread wheat grown in western Washington.

Caitlin Price, PhD student in the wheat program received the Alexander Smick Scholarship for Rural Community Service and Development. Caitlin is working on a PhD to study the bio-solids composting process, and application of bio-solids compost to crops in Skagit Valley.

Ziduan (Paul) Han, Masters student in the small fruit horticulture program earned a $2000 scholarship from WSU’s Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture. He is focusing on root lesion nematode control in red raspberry.

Emily Gatch, PhD student in the vegetable seed pathology program has been awarded the 2012 Maguire International Seed Technology Fellowship from WSU. Emily’s PhD research project focuses on fusarium wilt management in an effort to enhance the viability of spinach seed production in the U.S.

Entomology researchers provide new pest management options for Northwest small-fruit growers

When it comes to small fruit pest management, there’s no simple solution to address all the crop-damaging insects which emerge each spring and summer. However, Entomology Program Leader Lynell Tanigoshi and his colleagues at the Washington State University Mount Vernon Research and Extension Center have devised an effective system to help growers control what is considered among soft fruit growers to be “Public Enemy No. 1” – spotted wing drosophila.

The system: Insect Resistant Management (IRM), which utilizes rotational calendar sprays and divergent chemistries to reduce resistance to insecticides after repeated use. This provides growers with some science-based choices for protecting their crops.

“Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) has established itself as the most economically damaging pest to blueberry and caneberry production in the Pacific Northwest, if not controlled by insecticides through a rotational calendar spray program,” said Tanigoshi. “To maximize market flexibility, growers should initially adopt the most restrictive spray program, followed by a cautious re-introduction of insecticides to meet changing field conditions and market demands.”

Tanigoshi’s advice is part of a report, “Spotted Wing Drosophila in Berries – 2013 Findings,” which he and fellow entomology team members Associate Entomology Professor Beverly Gerdeman and Agriculture Research Technologist Hollis Spitler compiled for this month’s edition of Whatcom Ag Monthly, a newsletter published and distributed by WSU Whatcom County Extension. Tanigoshi and his team have been presenting their findings to growers, researchers and small-fruit industry supporters throughout lower British Columbia and northwest Washington and Oregon. Their most recent presentation was part of the Horticulture Growers’ Short Course, sponsored by the Lower Mainland Horticulture Improvement Association, at the Pacific Agriculture Show held January 30 – February 1 in Abbotsford, B.C.

The SWD report is a result of the team’s WSU Mount Vernon Small Fruit Pest Management Program research, which focuses on new and cost-effective ways to help Washington state’s $100-plus-million small fruit industry deal with arthropod pests that can wreak havoc on the more than 30,000 acres of blueberries, red raspberries, and strawberries grown here.

Arthropods are invertebrate animals which have an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and jointed appendages. Although they can play a beneficial role in the life cycle of a garden, when out of balance with their natural predators or outnumbered by an invasive species, Tanigoshi said, they can quickly decimate a grower’s marketable crop yield.

Spotted wing drosophila, which originates from temperate China and Japan, is a small fruit fly related to what are commonly known as vinegar flies. The female spotted wing drosophila has evolved with a specific appendage, known as an ovipositor, which enables it to deposit its eggs under the soft skin of blueberries, red raspberries and strawberries.

According to Tanigoshi, SWD is a major concern to growers, because – unlike vinegar flies which are attracted to rotting fruit on the ground – this fly goes after fruit that is still ripening on the bush. “She (SWD) is in the bush and feeds on ripening berries rather than rotting fruit,” Tanigoshi said. “Her larvae then feed inside the berries, causing the fruit to soften, leak fluid, and discolor which significantly reduces the quality and market value of those crops.”

Tanigoshi’s team has been focused on this arthropod pest for the past four years, due to the threat it poses to the region’s small-fruit industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics show that the blueberry harvest alone in Washington and Oregon for the 2012 growing season accounted for 15,900 acres worth a total value of $192 million in fresh and processed fruit. The red raspberry harvest accounted for 11,000 acres worth $44.5 million, followed by 3,300 acres of strawberries valued at $25.3 million.

“Spotted wing drosophila is the first direct pest to attack the berries, as opposed to indirect pests like weevils, which attack other parts of the plant such as the roots, stem, and leaves,” Tanigoshi explained. “This exotic insect invader (SWD) justifiably scared growers and resulted in the USDA’s zero tolerance policy toward the presence of this fly in fruit. Even if just one larva is found in a 2-pound sample of product, the entire berry harvest cannot be processed.”

According to Tanigoshi, intervention at various stages of this and other small fruit pest life cycles is the key to helping growers minimize their losses.

“Bev, Hollis and I are developing the idea of the cumulative effects of pesticide applications on the calendar schedule,” said Tanigoshi. “We’re trying to establish a bio-fix for growers to be able to begin their pesticide treatments when berries are actually ripening, and then – based on their specific crop and growing conditions – apply applicable pesticides every six to eight days through harvest.”

The goal is to find intervals when pesticide applications are not needed and to determine what rotations work best for the growers, Tanigoshi said.

“After four years of fighting this insect, we better understand the biology and behavior of spotted wing drosophila,” he added. “We’re trying to educate people to make intelligent choices based on scientific evidence, so we can move in the direction of finding more ways to get off our addiction to calendar sprays.”

Currently, there are nearly a dozen effective chemical controls available to battle SWD, said Tanigoshi.

“Growers are in good stead for the near future,” he said. “Our arsenal is sufficient. The key is to be selective and precise based on sampling, so they can determine for themselves, ‘Do I pull the trigger or not?’ with regard to pesticide application. Our research has shown that if growers follow the label instructions and use these chemicals properly, they shouldn’t have a problem with SWD.”

According to Tanigoshi, the next step will be to develop new mode-of-action insecticides against SWD that will prevent insect tolerance and target different sites in order to interrupt the fly’s reproduction cycle, which in the Northwest can be as rapid as three to four generations hatched each year.

“At the risk of sounding sexist, a large part of our efforts will be aimed at fighting the female of this species, because she’s the one depositing the larvae in the fruit,” said Tanigoshi, whose Small Fruit Pest Management Program is not limited to battling SWD.

“Our program includes regional and international components and endeavors to improve the quality of food and health of farmers and consumers here and in developing countries,” he said. “Food safety concerns, water and environmental health along with increased costs of agrichemical protection, production and arthropod pest control tools are issues central to the program’s focus to enhance small fruit production in western Washington.”

Tanigoshi’s SWD work is funded largely by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Northwest Agricultural Research Foundation, the Washington State Department of Agriculture, the Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration, and Washington State Commodity Commissions.

More information about WSU Mount Vernon’s Small Fruit Pest Management Program is available at http://www.mountvernon.wsu.edu/ENTOMOLOGY/main/index.html. A copy of the SWD report is available athttp://whatcom.wsu.edu/ag/newsletter.html.

Volunteer groups cultivate WSU Mount Vernon’s one-of-a-kind public gardens

Taking their cue from the honeybee, volunteers at WSU Mount Vernon’s public orchard and display gardens are doing anything but hibernating this time of year.

Starting with their annual Winter Field Day on March 1, members of the Western Washington Fruit Research Foundation were buzzing around the 6-acre orchard giving hands-on lessons in grafting, pruning and other fruit-growing topics.

The Fruit Research Foundation is one of three volunteer groups responsible for creating, developing, and managing the 8-acre Volunteer Display Gardens, situated just north of the research center.

The other two volunteer groups which collaborate with WSU Mount Vernon in maintaining the gardens are the WSU Skagit County Extension Master Gardeners and the Salal Chapter of the Washington Native Plant Society. Between the three groups, more than 100 volunteers log nearly 5,000 hours each year in designing, planting, cultivating, weeding, and maintaining this unique assortment of gardens, which are on display to the public daily from dusk until dawn.

“Many of the volunteers have been working in the gardens since they were established here in the 1990s,” said WSU Mount Vernon Facilities Manager Dan Gorton, who serves as liaison between the research center and the volunteer groups. “To my knowledge, none of the other research centers or campuses have this type of close working relationship with volunteer-based gardens or groups.”

The uniqueness of the display gardens extends beyond their design and plantings. It’s all about the relationships which have grown throughout the years between the research center, the volunteer groups, and the community.

“Each group holds different events each year to share what they have to offer with the public above and beyond the gardens they display,” said Gorton. These events include plant sales conducted by the Master Gardeners and the Native Plant Society which provide plant materials to the public and serve as fundraisers to help defray garden maintenance costs.

“The Master Gardeners also hold trainings and ‘Know and Grow’ lectures that are open to the public and held in our Sakuma Auditorium,” Gorton said. “The upcoming Winter Field Day is one of two such annual events held by the WWFRF that have both indoor training and outdoor hands-on learning or picking of fruit.”

According to Gorton, all the volunteers share a sense of pride in the work they do on behalf of the gardens, the University, and the visiting public.

“The garden groups are essentially a guest on WSU property, but they all take ownership in the care of their gardens and work with an inspiring spirit to share with the public both their knowledge of gardening and the beauty they have created,” Gorton said.

“The people really do make these gardens what they are, and many of the volunteers also step up each year and help with WSU events such as the annual Kneading Conference West (now known as The Grain Gathering), which attracts more than 300 people,” he added. “Many event activities actually occur in the gardens and showcase – to attendees from all over the United States, Canada, and the world – just how incredible these gardens and the people who maintain them really are.”

The Fruit Research Foundation, which encourages organic growing methods, was created in 1991 to assist with tree fruit varietal research being conducted at that time at the research center. The fruit garden/orchard was designed and created by WWFRF members in order to allow the public to view successful fruit varieties and cultural methods for the Pacific maritime climate. The fruit garden features oval plantings of heirloom apples, fruits recommended for this area, nuts, stone-fruit trees as well as arbors for wine and table grapes, kiwis, and other vines and examples of espalier designs and ornamental/edible landscaping.

The Discovery Garden was first envisioned in 1994 by the WSU Master Gardeners in order to interest, inspire and educate the public; develop a garden for community use and enjoyment; and enhance the quality of the Skagit County environment. After two years of planning, its initial structure was established in 1996. Visitors here now wind through a variety of Pacific-Northwest-themed displays, ranging from a shade garden to hot and cool color borders, an evergreen corner, an ornamental grass garden, seasonal gardens, a cottage garden, an herb garden and even a children’s garden – complete with ABC and fairy gardens, a waterfall and a maze.

The half-acre Native Plant Garden nurtures the seeds for future lower Skagit Valley native plants. It was created 15 years ago by the Salal Chapter of the Washington Native Plant Society and has evolved to include a multi-layered garden canopy of trees and shrubs, extensive mounds supporting native plants of varied textures and colors, and a pond hosting its own non-native resident bullfrog population and the occasional Great Blue Heron.

Gorton said the gardens allow the community to “share a piece of the research center and showcase what can be grown in our maritime climate.” One example of the impression the gardens have had on the community is the fact they are now an official stop on the annual Skagit Valley Tulip Festival Tour Map, he said.

“The gardens help bridge gaps between the intricate detail of scientific research occurring at WSU Mount Vernon, commercial-scale production agriculture, and the home gardener who represents the majority of our population,” said Gorton.” said Gorton. “We are all dependent on one another.”

People who would like more information or are interested in volunteering at the public gardens may contact the following organizations:

Western Washington Fruit Research Foundation:

Sue Williams, President, info@wwfrf.org, 206-383-8033,

website: http://nwfruit.org/

WSU Master Gardeners Program:

Sacha Buller, Coordinator, sachab@co.skagit.wa.us,

360-428-4270 x227, website: http://skagit.wsu.edu/mg/

Washington Native Plant Society Salal Chapter:

Susan Alaynick, Chairperson, s_alaynick@hotmail.com,

360-659-8792, website: http://www.wnps.org/salal/